New research shows readers prefer writing from artificial intelligence (AI) models trained on specific authors’ complete works over human experts trying to match the same style. The finding comes amid numerous copyright lawsuits in which AI companies claim that training on books falls under fair use.

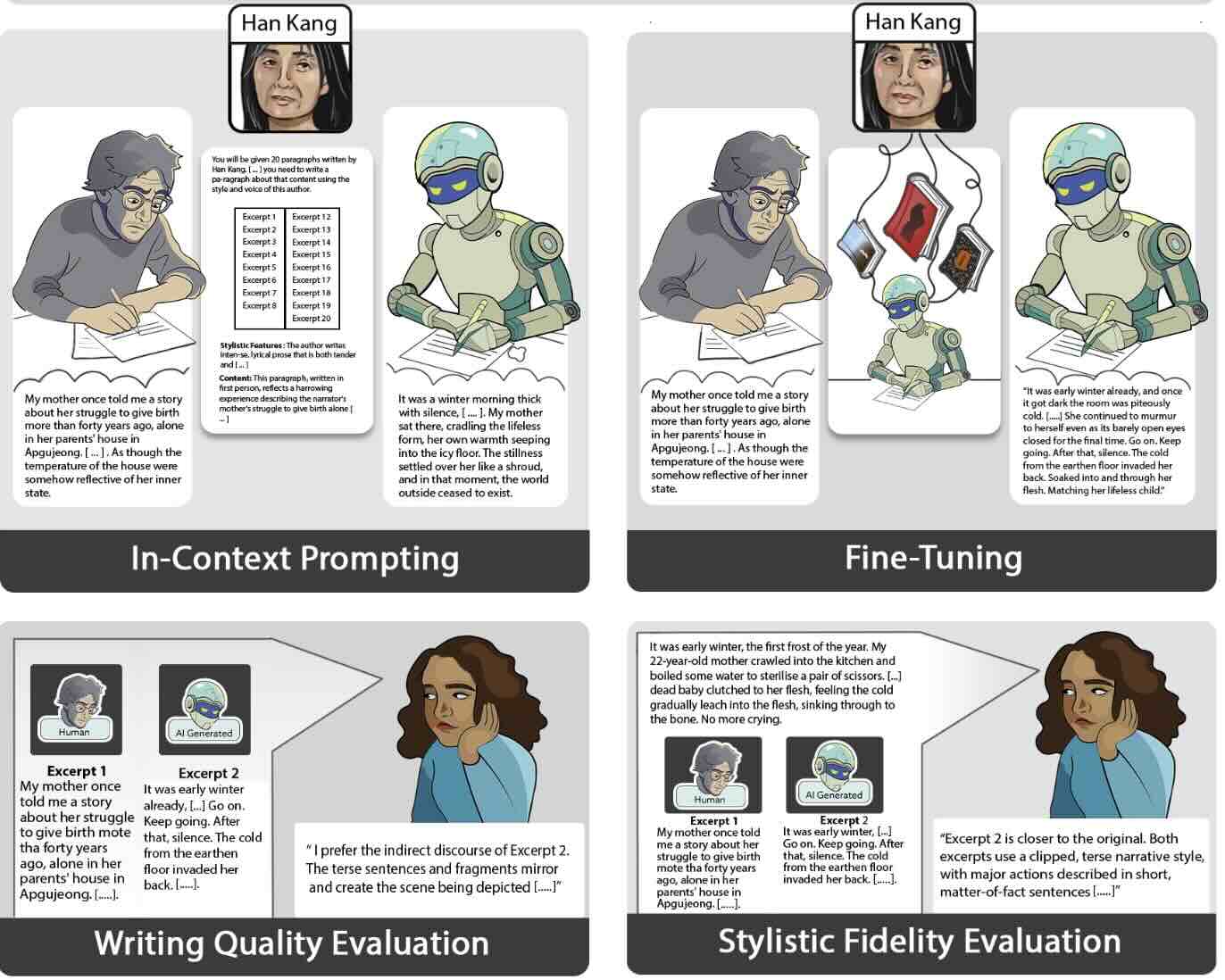

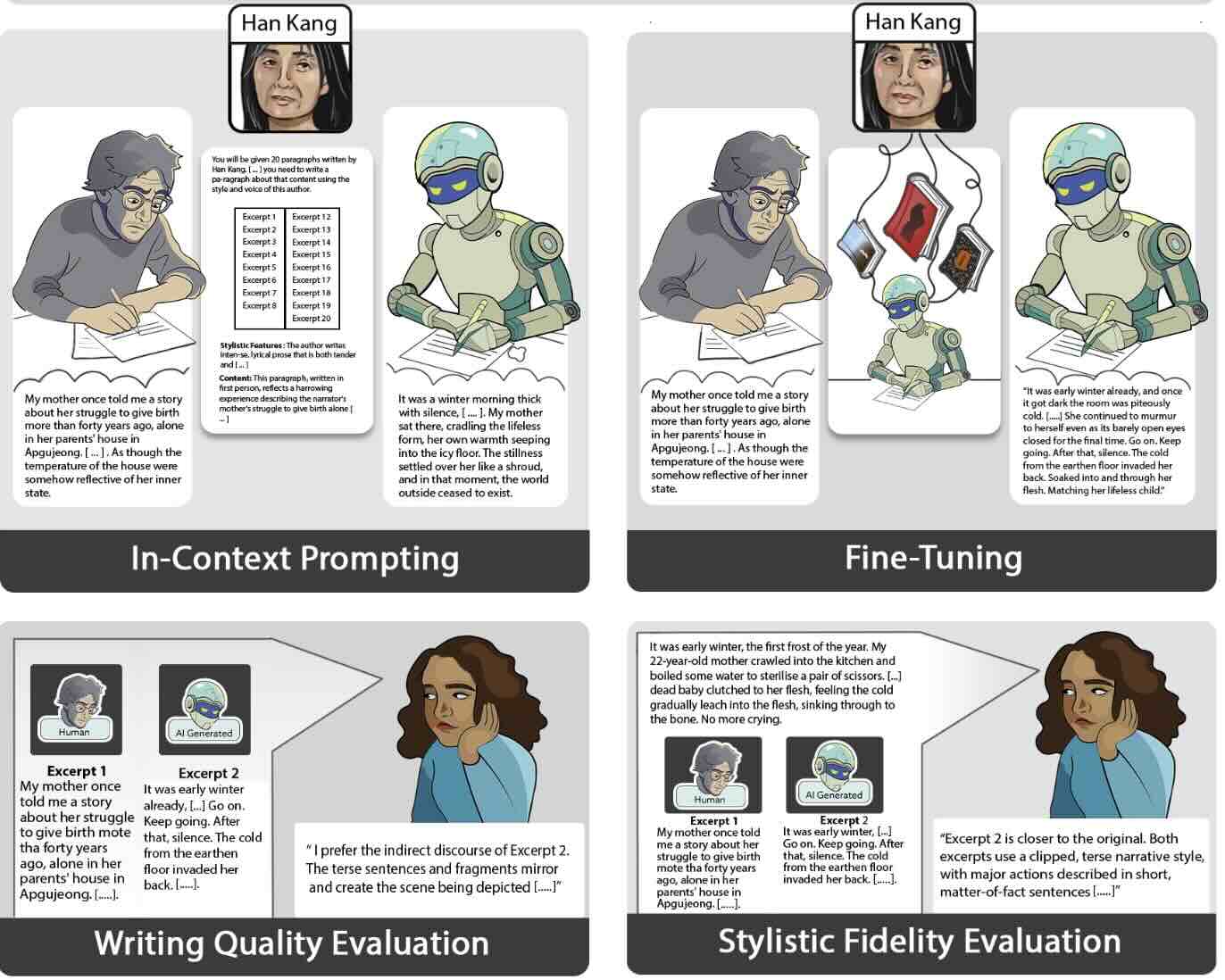

Researchers from Stony Brook University, Columbia Law School, and the University of Michigan tested whether AI could match the output of professional writers. They recruited 28 candidates from top Master of Fine Arts (MFA) programs and asked them to write excerpts that imitated 50 award-winning authors.

The MFA students competed against three AI models: ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini.

Expert and lay readers strongly preferred human writing when AI used standard prompting. But everything changed after researchers fine-tuned ChatGPT on each author’s complete published works.

Fine-tuning completely reversed reader preferences, the study found. Expert readers gave fine-tuned AI an eight-to-one preference for style matching. They also rated AI-generated writing quality nearly twice as high as human-generated writing.

Source: Readers Prefer Outputs of AI Trained on Copyrighted Books over Expert Human Writers

Co-author Paramveer Dhillon said reader preference for AI text over human writing, combined with low production costs, means AI literary works could compete with and even displace human-authored works.

Fine-tuning a model and generating a 100,000-word manuscript costs around $81. A professional writer charges approximately $25,000 for the same work.

The research comes as Anthropic recently settled a copyright lawsuit for an estimated $1.5 billion. Authors sued after the company trained its Claude model on millions of books downloaded from pirate sites. A California judge ruled the training itself was a fair use, but acquiring books illegally was not.

Copyright law allows fair use based on four factors. The fourth examines “the effect upon the potential market or value” of original works.

Courts traditionally focus on whether AI outputs copy the original text verbatim. The researchers argue this misses the point.

“The Copyright Office’s expansive interpretation suggests that fair use might not excuse predicate copying even when it doesn’t show up in the end product, if the copying’s effect substitutes for source works,” they wrote.

Fine-tuned AI also evaded detection. State-of-the-art AI detectors caught 97% of standard AI writing but only 3% of fine-tuned output.

The study included Nobel laureates, Booker Prize winners, and Pulitzer Prize winners among the 50 authors tested. Performance showed no connection to how much text was used for training.

Former Meta executive Nick Clegg recently said requiring permission to use copyrighted material would “basically kill the AI industry in this country overnight.”

The researchers suggest a middle path. General-purpose models trained on broad datasets might qualify as fair use. But creating author-specific fine-tuned models to generate competing works should not.

“These findings suggest that the creation of fine-tuned LLMs consisting of the collected copyrighted works of individual authors should not be fair use if the LLM is used to create outputs that emulate the author’s works,” the paper concludes.

More than 50 copyright lawsuits against AI companies are currently pending in U.S. courts.